Each year the KBS LTER program awards one full-year Graduate Student Fellowship. Here Leah Harris Palm-Forster describes her research that was supported by the 2014 LTER Graduate Fellowship. Leah obtained her Ph.D. working with Professor Scott Swinton in MSU’s Department of Agricultural, Food, and Resource Economics and is now an Assistant Professor at the University of Delaware in the Department of Applied Economics and Statistics.

~~

Going once, going twice, … bought from the lowest bidder! Hold on, what kind of auction is that? Why is the auctioneer buying something and why does the lowest bidder win? It’s called a procurement auction, or reverse auction, and it is used to buy services from competing providers. Ok, interesting, but what does that have to do with ecosystem services (ES)? … This is the Kellogg Biological Station Long-term Ecological Research (KBS LTER) blog, right?

Many farmers need incentives to adopt conservation practices, according to past economic research at the KBS LTER. Payments for ecosystem services (PES) are one important form of incentive. But when conservation budgets are limited, what is the best way to use the funds?

KBS LTER graduate student Leah Harris Palm-Forster talking with farmers at a pilot auction in Paulding, OH in July, 2013. In the pilot auction, farmers participated in hypothetical conservation auctions so that we could test different auction designs before conducting the real auction in 2014. Photo credit: S. Swinton, MSU.

Procurement auctions can be used to target payments for ES on agricultural lands by getting farmers to compete for funding to use environmentally beneficial management practices (BMPs). Using auctions to allocate conservation funds is a novel way to increase ES provision with a limited budget. It allows us to target funding to the fields that can provide the most ES per dollar spent. But, for auctions to target payments effectively, farmers must be willing to participate. Farmers are typically familiar with bidding in auctions and they might bid on a sturdy tractor without a second thought. Some farmers are also familiar with the competitive auction process used to enroll land in the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) General Sign-Up. Unfortunately, participation in conservation procurement auctions for BMPs on working lands is often low. We want to understand why that is and work to improve the design of auctions so we can cost-effectively provide more ES with limited conservation funds.

First, let’s back up for a minute to understand how conservation auctions work. My opening line was a little deceptive because there is no auctioneer yelling out bids and choosing the winning bidder. Actually, after announcing a new conservation auction program, it can take several months to complete. First, farmers bid the amount of money they would want to be paid to implement a BMP. For example, farmers could bid to plant a cover crop, which is a BMP whose environmental value has been shown in recent KBS LTER experiments. Farmers are usually given a couple of months to submit bids via mail and the bid amounts are not revealed to others. Bids can be evaluated using simple scoring metrics or using complex biophysical or ecological models that predict how much environmental benefit (for example, reduced nutrient runoff) would be provided by a given practice, depending on where and how it would be implemented in the landscape. Depending on how bids are evaluated, the evaluation process can take a month or more. Bids are ranked and the “best” (most cost-effective) bids are selected for funding — these are bids for practices that provide ES at the lowest cost per dollar of conservation funding awarded. You can probably already tell that auctions are not a simple endeavor and getting a lot of bids during the open bidding period is key to success.

In our research, we analyze how conservation auctions can be used to cost-effectively improve water quality in the Lake Erie Basin. Spurred by agricultural phosphorus runoff, harmful algal blooms (HABs) in Lake Erie are a prime example of nutrient runoff wreaking havoc on water quality. HABs produce a toxin called microcystin that is dangerous to humans and wildlife, negatively affects ecosystem health, and degrades recreational amenities. Cost-effectively mitigating HABs requires an understanding of the ecology of the agricultural landscape as well as the behavioral and economic factors that drive land management decisions. Ah ha! That sounds like that type or research being conducted in the KBS LTER program.

With financial support from the KBS LTER research fellowship and the Great Lakes Protection Fund (GLPF), and in collaboration with The Nature Conservancy (TNC) and LimnoTech, we conducted two conservation auctions in NW Ohio during the summer of 2014. We invited 1,085 landowners to submit bids for practices that reduce excess phosphorus runoff, but only 1% of people actually submitted a bid. This resulted in funding some bids that provided little benefit to the environment, which meant that we paid a high price per dollar of reduced phosphorus runoff thus reducing overall cost-effectiveness.

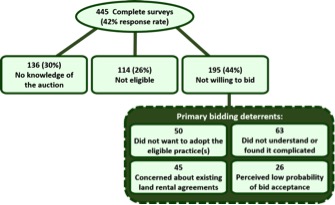

Why didn’t more farmers participate? We mailed a follow-up questionnaire to non-participants and got a 42% response rate (… whew, that’s certainly better than 1%). The follow-up survey revealed three chief reasons for non-participation in the conservation auction (Figure 1): 1) lack of knowledge about the auction (30%), 2) ineligibility (26%), and 3) unwillingness to bid (44%). Primary reasons for unwillingness to bid included, 1) not wanting to adopt the eligible practices, 2) concern about existing land rental agreements, 3) perceived auction complexity, and 4) doubts about acceptability of a planned bid.

Figure 1: Primary reasons that landowners did not participate in the 2014 Tiffin watershed conservation auctions in Fulton and Defiance counties, Ohio, were lack of knowledge about the auctions, ineligibility, and unwillingness due to lack of interest in adopting the eligible practices, existing land rental agreements, perceived low probability of bid acceptance, and confusion about the auction process.

Land rental and auction complexity both represent hidden “transaction costs” that require added time and effort on behalf of the farmer. Farmers respond to these added costs by either demanding more money to participate or being unwilling to apply for the program at all. Both outcomes undermine the cost-effectiveness of conservation auctions. A streamlined bidding process is needed to reduce confusion and to make it easier for farmers to participate. This is especially important to engage farmers in land rental agreements since nearly half of the cropland in the Lake Erie Basin is rented.

As I write this post, Toledo residents are stocking up on bottled water in preparation for the record-breaking HAB predicted by experts this year. We need more farmers to use BMPs that reduce phosphorus runoff, but most farmers require payments to offset the costs of these practices. Conservation auctions can help us cost-effectively fund the best BMPs if farmers are willing to submit bids and engage in the program. Future research will continue to determine how we can engage the farming community and identify programs that can be a win-win for both farmers and the environment.